When 18F started, deploying government services into a public cloud was still fairly uncommon. However, over the last two years nearly everything 18F has built for our agency partners has been deployed into Amazon Web Services (AWS), including our platform-as-a-service cloud.gov. Meanwhile, other federal agencies have also started using commercial public clouds, some at a large scale.

Over that time, as a result of the success of implementing the federal cloud-first strategy, 18F’s AWS account has grown in size and complexity. We need a new approach to ensure it remains manageable. In this post, we’ll describe our plan for evolving our existing cloud deployment based on modern DevOps principles and practices. Future blog posts will discuss how we are executing each part of our strategy.

If you’re a developer, architect, or sysadmin designing or managing cloud environments, we hope you’ll find something useful in the lessons we’ve learned. We welcome feedback and pull requests on the open source tools we’ve developed as part of our work.

Our goals

Since every organization is different, and even a single organization will necessarily change and evolve over time, there is no “one size fits all” solution to any given problem. Thus to plan our new approach we had to first agree on our goals. Our infrastructure team provides infrastructure-related services, training, support and tools to 18F delivery teams. Our mission is to enable 18F teams to meet their goal of helping government agencies ship high quality user-centered digital services to the public. In the context of our cloud infrastructure, we have a few high-level outcomes we want to achieve:

- Give everyone at 18F maximal access to cloud resources while minimizing the required compliance processes.

- Straightforward, transparent billing of costs to 18F and partner agencies.

- Ensure we can restore service quickly in a repeatable, deterministic fashion in the event of an attack or infrastructure failure.

- Manage the lifecycle of infrastructure resources, and the systems built on them, transparently in an automated fashion.

- Ensure our team can manage an ever greater demand for the services 18F provides and the systems it builds without burning out our team or slowing the pace of innovation.

Finally, our higher-level goal is to provide a reference for modern DevOps cloud practices in government — in particular, treating infrastructure as cattle, not pets. 18F doesn’t have enough capacity to work with every government agency, but by creating open source tools and discussing the principles behind them we can reduce the friction for other teams working to build cloud-native systems in government.

Our plan

First, we want to move as many of our systems as possible into a platform-as-a-service (PaaS). By using a platform, we can reduce how long it takes to release new services by taking care of the majority of the compliance concerns that must be addressed by federal government systems at the platform layer. Because we believe that “eating our own cuisine” is critical to creating high-quality products, we’ve chosen cloud.gov — a PaaS which 18F is developing in the open using open-source components — as our platform. In addition to building a platform, the cloud.gov team is working hard to reduce and automate both the technical work and documentation required to deploy new systems. cloud.gov is currently on track to be certified for use by most types of government system by the end of 2016.

However, a small minority of systems won’t be able to initially run on cloud.gov. For example, AWS GovCloud meets the government threshold for systems with high risk levels, but cloud.gov doesn't — yet! Other systems may not fit neatly into the architectural patterns that cloud.gov uses. For those systems, we’ve created a fully automated deployment pipeline on top of our new, controlled AWS accounts, deployed using a tool called Raktabija.

Everyday users do not have credentials to our new production account. Instead, any systems hosted in the environment will be deployed automatically using scripts without any human intervention. In this way, we ensure folks aren’t creating systems that are hard-to-maintain snowflakes. Furthermore, if we need to restore service in the event of a catastrophic failure, we can do so in a fully automated and deterministic way. Finally, any systems deployed into this environment will run in auto scaling groups. This ensures that if an individual server fails, a new server will spin up automatically without any interruption to service. By deploying regularly from scratch we also eliminate configuration drift and ensure our attack surface is a constantly moving target.

We also want to make it easy for people to experiment with cloud infrastructure, test their systems in a production-like environment, and run ad-hoc tasks like data crunching. Thus we’ve set up a sandbox account in AWS and given everybody in 18F the ability to spin up whatever services they’d like, subject to a few restrictions. We’re keeping this environment under control by deleting everything in it automatically at the end of the week using a script which is installed and run automatically by Raktabija.

Patterns for managing cloud environments

We’ll talk about the new production account and sandboxes in more detail in future articles, but we wanted to highlight a couple of important patterns we’ve applied in our strategy.

First, the principle of disposability. When we work with cloud infrastructure, we’re necessarily building distributed systems. This, in turn, requires a critical shift in both our mindset and our architectural and risk management principles. In internet-connected distributed systems, we must accept that failures and security breaches are inevitable. Thus we change the focus of our work from trying to prevent outages or attacks to developing the capability to detect them and restore service rapidly. To prove we can withstand failure, we continually inject it into our systems, proactively attacking our infrastructure — a key principle behind cloud disaster recovery testing exercises and Netflix’s Chaos Monkey, known as chaos engineering.

Systems built on cloud infrastructure must assume the infrastructure is unreliable. Thus to meet our goal of being able to restore service rapidly in the event of failure, we should treat it as disposable, ensuring we can rebuild it from scratch automatically using only configuration and scripts held in version control. To this end, every system and resource in our AWS accounts has an expiry date, and gets deleted automatically if that expiry date is not extended by a person. Expiry dates are short — one week — in the case of the sandbox account, and longer — of the order of months — in production accounts.

To extend the expiry date and prevent infrastructure and the systems sitting on them being garbage collected, you must register the system — and its owner — in Chandika, our system registry (see below). In this way, we can ensure we can trace every resource in every account to the system it belongs to and the owner of that system, and bill the operational cost of that system correctly. We also prevent our AWS account from becoming cluttered up with zombie infrastructure — random servers, S3 buckets, or load balancers whose purpose is unknown but which we must continue to pay for in case turning them off causes the failure of some critical system.

The second pattern we’ve applied is the strangler pattern / encasement strategy. In this pattern we replace existing systems incrementally, rather like a tropical strangler fig growing around a tree and gradually killing it. At the beginning of this journey, all our production systems (including cloud.gov), along with several systems under development, were running in the same AWS account. Our first step was to create new accounts: one for cloud.gov, another for non-cloud.gov production systems, and a third for the sandbox. Over the coming months we’ll continue to gradually move systems over to these new accounts, and then turn off infrastructure in the old account. Once everything is moved out, we’ll decommission it.

Tools for everyone!

Here at 18F, we’re an inveterate community of tinkerers, and no technical blog post would be complete without announcing some new open source tools. If you’re interested to see what we’re building, head over to 18F’s GitHub repositories and check out Raktabija and Chandika, along with the guides we’ve written to using our sandbox and production environments.

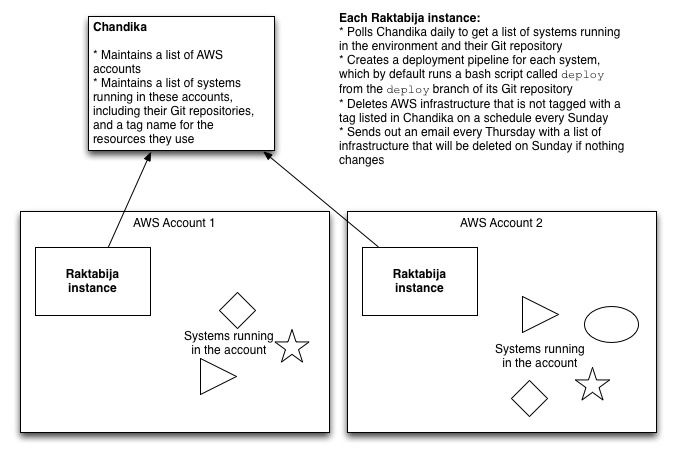

Raktabija is a tool that prepares new AWS environments, both production and sandbox. It bootstraps itself by creating a machine image with the tools to make further changes to the account, including a continuous integration (CI) server; configures the infrastructure with terraform; and then deploys this machine image. In production environments, the CI server deploys any services that run in the environment.

In non-production environments, the CI server acts as a cron-style scheduler that runs a script called Kali at the end of every week. Kali deletes everything in the environment that is not registered in Chandika. This prevents cruft accumulating in sandbox environments, and teaches developers to expect — and design for — disposable infrastructure.

Chandika is a web app which can be deployed to cloud.gov, CloudFoundry, or Heroku. Chandika acts as a registry for all services you’d like to keep in your AWS accounts. Chandika exposes an API that Kali consumes to find out which resources should not be destroyed. By deleting everything that’s not registered, we also nudge delivery teams to register the resources they’re using so we can trace every resource in AWS back to a system, effectively creating a shared, real-time cloud configuration management database (CMDB).

Raktabija also queries Chandika on a daily basis to discover which services are supposed to be deployed to the AWS account it manages. Raktabija will create a deployment pipeline for every service registered in Chandika that lists a Git URL, and by convention looks for and executes a bash script called deploy in the root of the deploy branch of that repository every time it detects a change in that branch. We’re already using this mechanism to continuously deploy our DNS configuration using terraform. In this way, DNS changes can now be made to several of the domains we manage simply by issuing a pull request.

These tools should be considered beta quality since they’re still evolving rapidly. As always, we welcome pull requests and feedback!

Thanks to ReferenceError: teamData is not defined, ReferenceError: teamData is not defined, and ReferenceError: teamData is not defined for comprehensive feedback on early drafts of this blog post

The web pages linked to in the article provided information for this post and readers may find them useful. However links do not represent an endorsement of these resources by 18F or the General Services Administration.