Last week we wrote about how we diffuse knowledge through shared interests and sharing best practices on the Micro-purchase Platform. This week, we’ll focus on some of the lessons learned during the (completed) DATA Act prototype. Importantly, though that project has finished, this post is not meant to be a full retrospective or post-mortem; we’ll be focusing on technical decisions. We should also delineate this from the more long term DATA Act broker, which is under active development.

What’s the DATA Act?

The recently minted Digital Accountability and Transparency Act (DATA Act) requires agencies to generate better public records about how the United States spends money. The law requires a common data standard for federal spending and that agencies generate their internal spending information against it. The U.S. Treasury Department released version 1.0 of this DATA Act Information Model Schema in April, 2016. The standard is expressed as eXtensible Business Reporting Language (XBRL), which is based on Extensible Markup Language (XML).

Developing the data standard proved challenging, as Treasury sought to include multiple perspectives and get consensus among several interagency communities. To ensure that DATA Act implementation could move forward as they worked towards the final data standard, Treasury:

- Released several draft versions of the DATA Act Schema

- Asked agencies to begin creating their DATA Act files against these drafts and test them using a “broker” prototype 18F worked with Treasury to develop

- Used agency feedback about the prototype to inform the next draft of the Schema and the ongoing policy discussions

Note: The prototype spotlighted here is specific to Treasury’s development of the DATA Act schema and should not be confused with the DATA Act Section 5 recipient reporting pilot, which is a separate effort being led by the Office of Management and Budget.

Minimum viable product

The real DATA Act effort for agencies is in connecting data sources that haven’t been joined before. However, a lot of the talk around the DATA Act was about technology like data lakes, data warehouses, and XBRL tooling. To ensure that agencies could focus on the important work of joining their internal systems without these unnecessary technology distractions, we (the 18F and Treasury prototype team) sought to deliver the simplest possible interface that would accept agency’s data using the simplest possible format for that data.

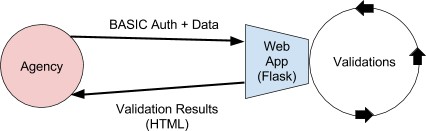

Our prototype contained two endpoints: one to display a form and one to accept input and report validation errors. There was no file storage, no authentication (aside from minimal Basic Auth), and no frontend build process. We deployed the prototype on cloud.gov and selected a familiar, Flask stack. From the beginning, we anticipated writing “throwaway” code, a simple demonstration that such an application could exist; we wanted to create that demonstration quickly with few resources. The application has been a routine reference point during DATA Act conversations long after the prototype ended, so we believe we were successful in achieving that goal.

The proof-of-concept focus is not without drawbacks, however. While we would argue that actively ignoring some best software development practices was the right choice for many of our decisions, the lack of test coverage ended up be painful as the project wound down. For example, during this period, we realized that the prototype didn’t work for error-free data submissions (the “happy path”). We discovered this error through manual testing, but could have avoided it altogether by writing unit tests from the beginning. In retrospect, this is a good example of why viewing code as “not real” can be a trap. We strongly recommend against falling into this trap; your small code base will quickly grow larger than anticipated and your early technical decisions have had long-lasting ramifications.

Simplicity avoids scaring away agencies

One of the earliest decisions our team grappled with centered on the data format we would receive from agencies. We ruled out XML/XBRL because we didn’t want its complexity to be a roadblock for agencies to use the prototype. After an initial attempt using Protocol Buffers (one cheeky engineer describes this as “a terrible decision”), we realized we needed to switch to something universally understandable before putting the prototype in front of people. Comma Separated Values (CSVs) fit the bill; they aren’t intimidating and are easy to export from existing spreadsheet software and database applications. With them, agencies could focus on finding the data, not encoding it.

Relevant data was submitted as four separate CSVs, each listing entries for one type of data. Think of it as a very rudimentary (and therefore approachable) set of four relational database tables, complete with foreign keys. Rather than defining a schema (or waiting for the official schema to be complete), we generated example CSVs to serve as templates. These were made available, along with the codebase, on GitHub, and would be referenced long after the prototype project completed. By defining a set of validations over these files rather than the difficult-to-generate-and-not-completely-defined XBRL schema, agencies could receive feedback about their data immediately.

In the final sprints of the prototype project, we implemented a simple, centralized conversion between the validated CSV files and the “final” XML/XBRL format, meaning that agencies could continue to work with a format they understood.

Validation rules

Two basic schools of thought dominate discussions of data standards. One holds that data validation should be defined along with the standard. Database schemas include constraints, XML files can be validated against an XML Schema Definition (XSD); by using the sophisticated rules of these and similar languages, one can prevent bad data from entering the system. The second camp argues that the standards are constantly evolving and need to remain flexible, that the validation rules are akin to unit tests for the schema. Further, the language of schema-based validations isn’t rich enough to support all of the rules needed. As we will be writing validation rules outside of the data format, why not keep the two separate from the beginning?

Drawing on our experience with similar problems in industry and knowledge that the XML/XBRL schema was still in flux, we aligned ourselves with the second camp. The rules wouldn’t live alongside the schema’s data definitions (and couldn’t easily, given CSV input), but we also didn’t want validation logic to live entirely in Python. Requiring developer intervention for all edits would be quite costly, particularly as the rules would be changing over the course of the prototype. If CSVs were a good common denominator for accepting data, perhaps they would be a good format for defining simple validation rules?

| fieldname | required | data_type | field_length | unique |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AwardandModificationEntryID | False | int | 25 | False |

| PlaceOfPerformanceEntryNumber | False | int | 25 | False |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

This approach proved to be quite handy. It enforced a very clean separation between “business logic” and the rest of the application. It also meant that maintaining these rules as the formal specification changed would be very easy. Editing rules was so easy, in fact, that our agency partner could maintain the rules themselves; they’ve modified these rules over time to fit new expectations. Additional fields could be added and rules applied to them all by simply editing a spreadsheet.

Of course, this scheme doesn’t scale forever. Certain requirements can’t be easily described this way, but these requirements were not encountered over the course of the prototype. We would have tried to tackle more complex validations in a similar manner, separating the rule logic from the data definitions. We gained so much value from the approach that we would work hard to extend it to new problems. Looking at how this problem is handled within industry, we can point to Google’s use of Prolog as a rule engine; while CSV rules aren’t as expressive, we share a declarative style.

Conclusion

The broker prototype that 18F built with Treasury was a tremendously successful prototype because it allowed Treasury to test their approach for collecting and validating DATA Act information quickly and inexpensively while getting feedback from agencies at the same time. Those learnings became the foundation for the long-term version of the DATA Act broker, which is now in beta and will be in production later this year. The new broker incorporates best practices like automated tests and deployment while retaining the prototype’s principles of a simple user interface, independent validation rules, short development cycles, and frequent releases.

Though this prototype had a very tight focus, it offers several interesting technical decisions which are worth sharing. Determining, at the outset, what a minimum viable product looked like and avoiding “production-ready” concerns like server load, malicious users, etc. allowed us to exceed our client’s expectations in short order. Building for a least common denominator (CSVs) gave the project reach (more users could participate) and reduced code complexity. Pulling out validation rules into a separate, easy-to-modify format made the product flexible and simple to maintain. Do any of these principles make sense for your project?

This document is the distillation of an architecture discussion between Aaron Borden, Jacob Kaplan-Moss, CM Lubinski, Micah Saul, Marco Segreto, and Becky Sweger. For more information about the DATA Act prototype, see the prototype repo on GitHub, particularly their screencasts.