If you follow DevOps trends, you have likely heard of infrastructure as code. Tangibly, infrastructure as code means having things like your network configuration, server attributes, access control, etc. in a machine-readable format. This code then:

- Serves as the source of truth for what the infrastructure should look like

- Can be used to recreate the infrastructure from scratch

- Is under version control

- Is modified by pull requests

DNS is a major piece of shared infrastructure at the Technology Transformation Services (TTS, which 18F is part of), which made it a prime candidate for infrastructure as code. Of the many benefits, doing DNS changes through pull requests rather than tickets brought turnaround time down from multiple days to under ten minutes.

What’s DNS?

TTS manages DNS for a number of domains. When you visit somewebsite.gov, DNS tells your browser which server to query for the website. Think of DNS like a phone book for the internet, mapping names to numbers (in this case, hostnames to IP addresses). As an example, the output below shows that 18f.gsa.gov points to a CloudFront CDN domain, which in turn points to a handful of IP addresses.

At many government agencies, a central IT team manages DNS directly. Other teams must request changes using help desk tickets, which:

- Can have inconsistent turnaround times

- Are susceptible to human error, since the changes usually need to be copied by hand from the ticket to the DNS management console

Enter: The DNS repository

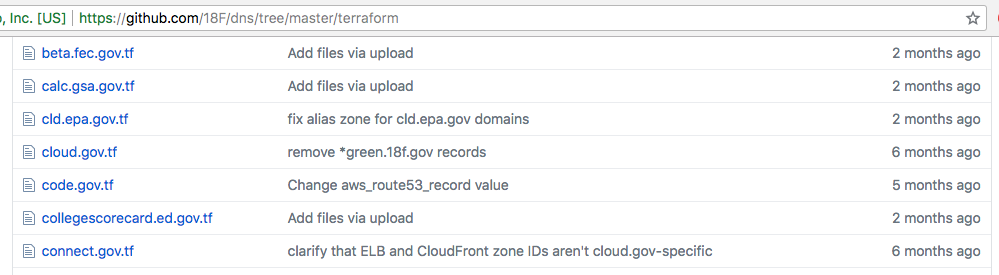

TTS applied the principles of infrastructure as code and open by default to DNS and placed all of our records in a GitHub repository. The records themselves are written in Terraform, an open source language and tool for describing infrastructure resources.

Having the code public means that anyone (inside or outside of TTS) can go through and see immediately what domains we manage as well as how they’re configured, all in one place.

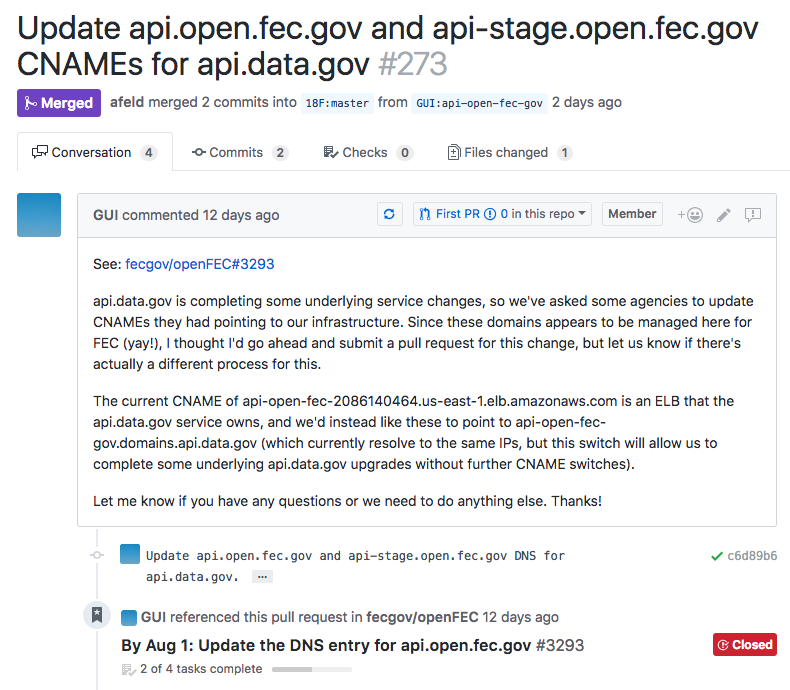

Changes to records are made by pull request.

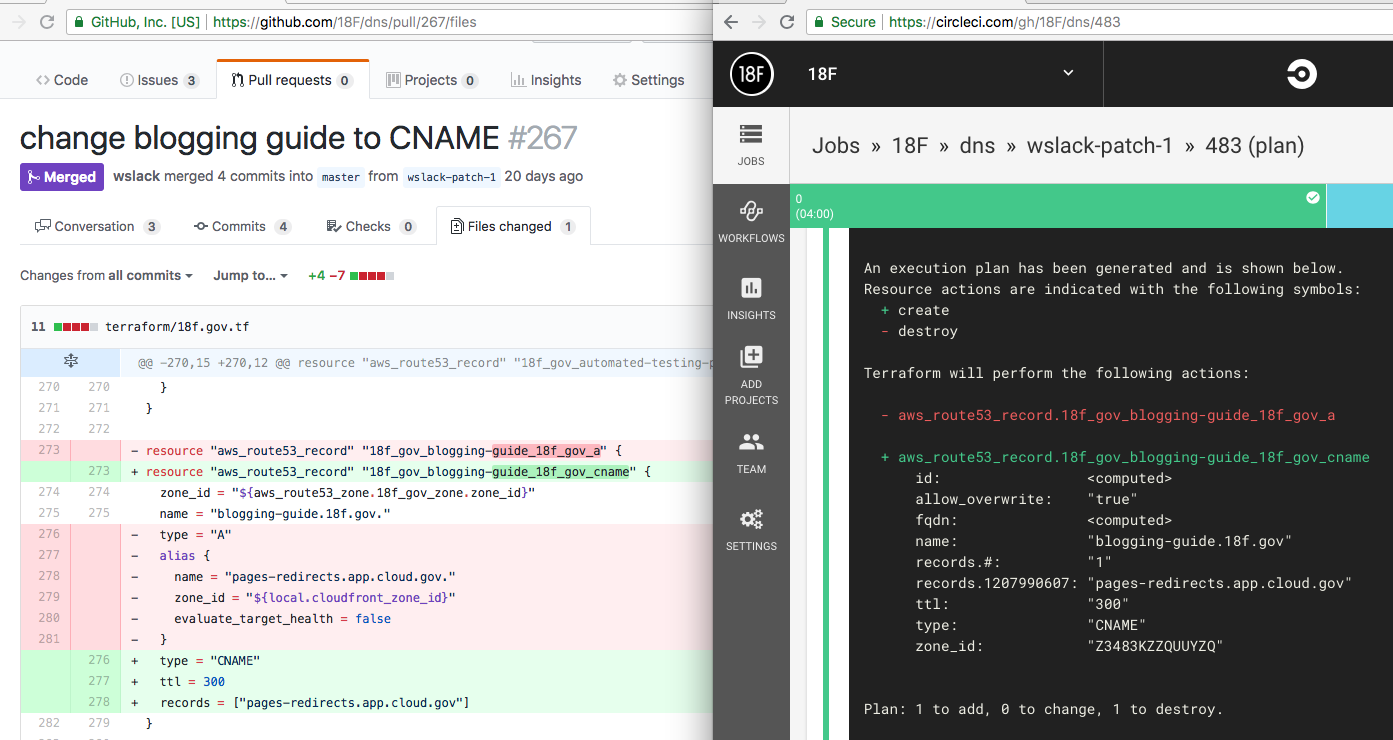

After submission, changes are checked automatically via continuous integration (CI) in CircleCI.

While this is mostly checking for simple things like valid syntax right now, we have ideas for expanding, like reporting unused records.

Before merge, someone looks over every change, even if it’s just a sanity check. Merging a pull request triggers an automatic deploy of the new DNS settings to Amazon Route53, which is where the live DNS records (name servers) reside. While this process is like submitting a ticket, administrators don’t need to manually enter any changes.

With the Terraform code in Git, we get all the benefits of version control, particularly an auditable history, attribution, and the ability to “undo”. (“Who changed this record? When? Why? That broke things...let’s take it back to how it was before.”) If our live records get deleted somehow, the next deploy puts them back in place exactly as they were.

Migration

Earlier this year, we needed to move our DNS records to a new Amazon Web Services account. Manually copying and verifying these records by hand would have been a tedious process. On top of that, we had to maintain all records in both places during the migration.

With the configuration in code and version control, we were able to modify our continuous deployment so that every change to the records was deployed to the old and new accounts.

The declarative nature of Terraform means that you tell it what state you want the infrastructure to be in, and it figures out what changes to make to get there. On its first run against the new account, Terraform saw that none of the records were in place, so it created them. Time from zero to hundreds of records present in the new account? A half hour.

With the records in both accounts, we gradually transitioned our domains to point to the new nameservers in the new account. When complete, we simply removed the code deploying to the old account and deleted the old records.

What could have been a painful DNS migration was made calm and confident by infrastructure as code and continuous deployment. Better Living Through Automation!

Do it yourself

Having TTS’ DNS specified in code in a public repository with continuous integration and deployment has been unequivocally positive. If your organization doesn’t do infrastructure as code but is interested in trying it out, DNS is a great place to start. Public DNS records don’t contain any sensitive information, it’s easy to confirm that they are deployed correctly, and you can use basically any continuous integration and DNS providers (that have an API). Fork our DNS repository to get started!