Maturing your design research practice is a bit like honing your skills at cooking. Experienced researchers rely on a refined set of sensibilities, or tastes, in their use and application of research methods; they create, curate, and refine informational recipes that turn raw data into palatable insights. And just like cooking, everyone can improve in their research abilities with a bit of reflective practice.

In this article, I’ll describe two exercises that I’ve recently encouraged at 18F to promote reflective practice around design research. I’ll address some of the challenges I’ve faced and the benefits I believe we might realize in encouraging routine reflection.

Exercise 1: Moderated research critiques

A few months ago, I watched a video of someone moderating a usability test in a way that I considered to be non-ideal. While my initial inclination was to give this person direct feedback, I eventually decided against it for fear that my feedback might not be well received; this person did not claim expertise as a research moderator, and I did not want to discourage them. Instead, I started to wonder how I might normalize an environment in which a researcher might expect to receive constructive criticism. I decided to run a “moderated research critique” and submit my own work for review.

What it is

A moderated research critique is one part asynchronous master class and one part fishbowl exercise. It’s performed with two goals in mind: The master class-inspired part effectively asks the question “how might I moderate research better?” The fishbowl exercise-inspired part helps build the team’s awareness of the skills and sensibilities that go into good research moderation.

How it works

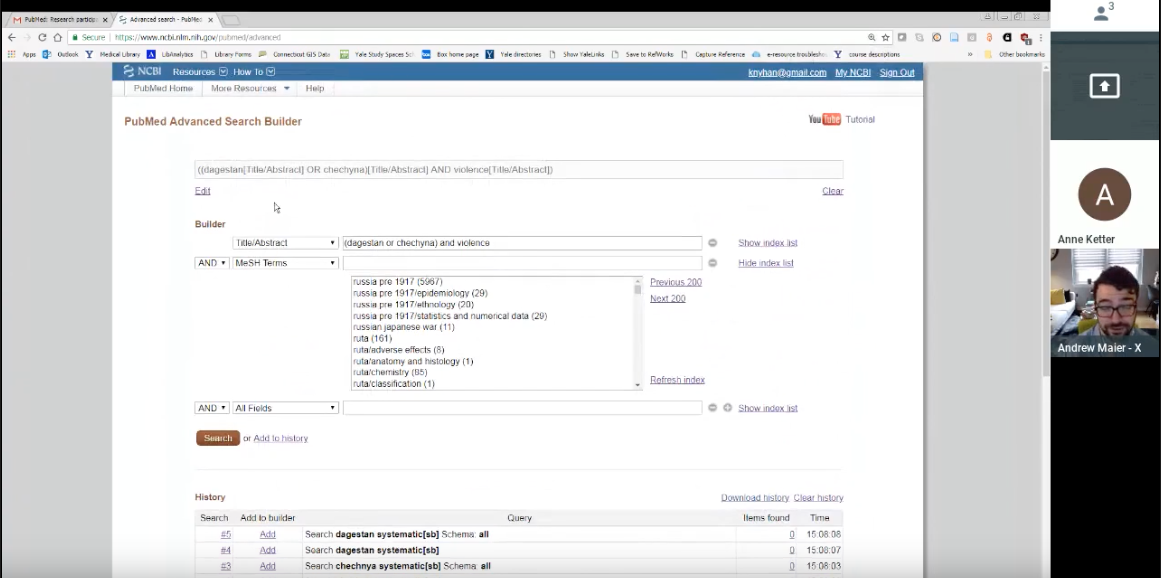

First, record a video of yourself or a teammate moderating a research session (for example, a user interview or a usability test). In this case, I chose a video of myself moderating a usability test from the same study as the aforementioned video I took issue with.

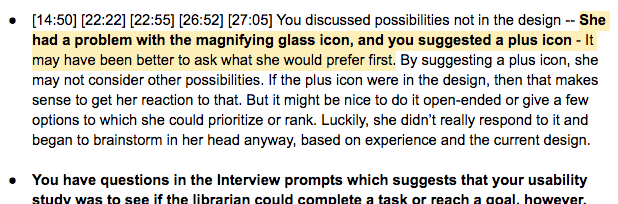

Second, ask another researcher, ideally someone more experienced than yourself, for feedback on your performance — specifically, time-stamped feedback. In this case, I sent the video of my session to my 18F colleague Victor Udoewa. I also shared with him the research plan for this study and the “interview prompts” I’d used to guide my moderation. Victor replied with the times where he thought I moderated well and times I might have done better (for example, when I suggested alternate UI designs after observing my participant struggle at completing a task).

Third, socialize the performance-related feedback you receive. In this case, I passed my recording and the time-stamped feedback I received along to other designers in my 18F critique group. 18F designers are divided into four-person critique groups that usually meet for 30 minutes a week. Discussing my moderated research performance was of interest to this group because 18F designers view research as a team sport — each designer will occasionally find ourselves in positions where we’ll need to moderate research!

Many critique groups critique artifacts rather than videos of researchers moderating interviews (making this more like an asynchronous fishbowl exercise). Time-stamped feedback is an especially useful starting point for scanning the video to specific parts and soliciting additional feedback and discussion.

Exercise 2: Research review

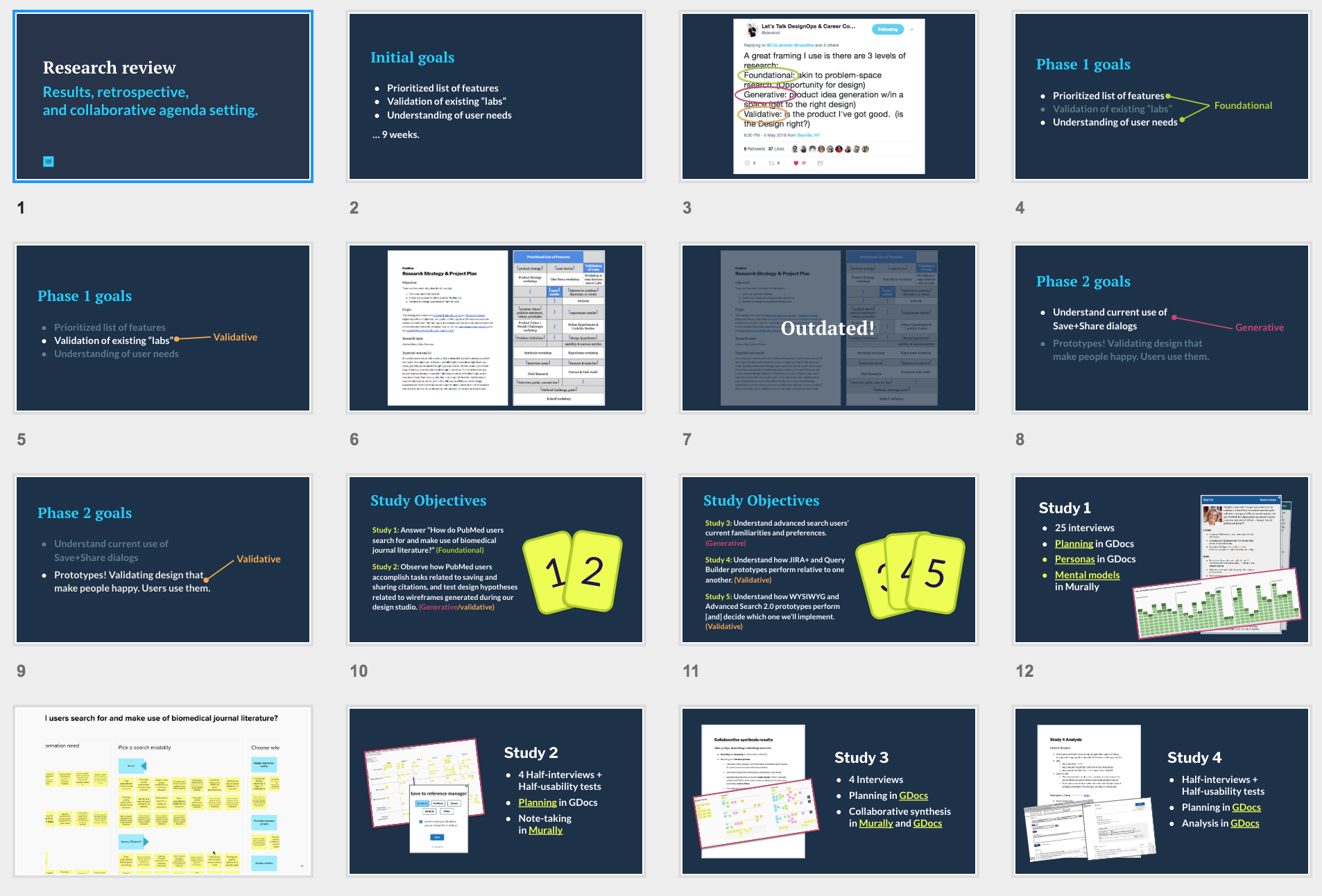

More recently, I found myself four months into what ultimately turned out to be a five-month, research-led engagement. This engagement began with foundational research. Over a two-month period, my colleagues and I conducted over 25 hours of stakeholder and user interviews. At the end of this research, we prepared a veritable cornucopia of deliverables: a mental models diagram and personas as well as a vision, mission, and a set of values and design principles for the agency’s flagship product.

In the following months, this engagement transitioned to a “lean UX” approach of building, measuring, learning. My colleagues and I held internal bake-offs in which design studios gave way to dot voting sessions and prototyping. Once we’d built enough to put in front of users, we conducted validative research — usability testing — to determine whether our ideas were too hot, too cold, or just right.

As I approached the end of this engagement, I began to wonder how I might encourage the team to reflect on the pros and cons of how we’d scoped our various studies. With an in-house usability lab and full-time staff dedicated to research, our agency partners were well versed in moderating usability tests. I began to wonder how I might help them reflect on how — and how often — they might conduct broader research going forward? This led me to hold a research review.

What it is

A research review is a research-focused facilitation exercise that encourages the team to reflect on its recent studies to inform its approach to future ones. The goal is better, more collaborative research.

How it works

A research review proceeds in two parts. In the first, the product team reviews the design of and findings from recent studies (a natural prerequisite here is that you’ll need to have conducted a few studies beforehand). In the second, the team conducts a retrospective focused on research practices.

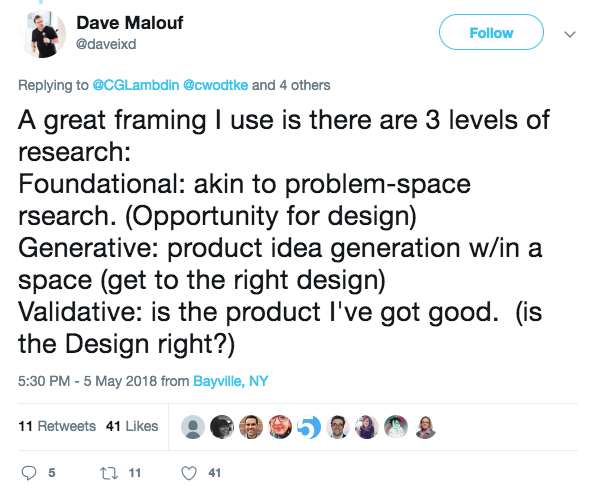

As I mentioned, this was a five-month engagement that began with two months of foundational research and concluded with three months of generative and validative research. My hunch was that while this approach was commonsensical for 18F, it was likely not as intuitive to our agency partners; if my own progression as a researcher says anything, people who are new to research are more likely to understand why and how they might do usability testing than why and how they’d do foundational or generative research.

For that reason, I framed our review with a tweet by Dave Malouf describing research across various levels:

I also shared this local-maxima diagram I learned about from Joshua Porter’s 52 Weeks of UX.

I explained that foundational research is useful for breaking out of “local maximas” and understanding the landscape in which the team is designing. Generative and validative research, on the other hand, is useful for making sure we’re moving in the right direction (i.e., up the mountain).

Next, I reviewed the design of the four studies we’d conducted. I described the problem statements that framed these studies, the methods we employed, the insights we gained, and the design decisions we made.

Summarizing our research to date put us in a great position to do a practice-related research retrospective. After inviting the team to a shared document, I asked everyone to spend two minutes each answering the following questions:

- Liked: What have you liked about the research we’ve done so far?

- Learned: What have you learned about research?

- Lacked: What are we missing or forgetting?

- Long for: What’s inhibiting your office from doing more research like this after 18F leaves?

To conclude the session, we did a quick dot vote (everyone got 4 dots to assign per question) to identify the team’s points of agreement. I ended the session by facilitating a conversation in which the team identified ways they might improve their research by incorporating more foundational and generative research.

Yes, chef

While the primary benefit of these exercises is becoming a better researcher, their social nature promises additional benefits. Specifically, routinely performing these exercises can:

- Demonstrate humility

- Encourage awareness that listening is a foundational part of a designer’s toolkit

- Encourage awareness of the subtle decisions that shape research

- Move conversations past “should we research” to “how can we research better”

- Potentially prevent frustrating experiences for participants (see this example)

- Help reduce biased study design

- Encourage alignment around study design

- Reduce the risk of overly optimistic interpretation (nods to Erika Hall)

- Potentially make findings more actionable

If you decide to give them a try, let us know how these exercises work for you at 18f-research@gsa.gov.

Note: Thanks to Dan Brown, Dave Hora, Anne Petersen, Steve Portigal, Jeff Maher, Brigette Metzler, Kate Towsey, and Victor Udoewa for providing feedback on an earlier version of this article.